Economic logic dictates that lowest-cost oil producers will survive longest once oil demand peaks, plateaus and starts to decline. In a shrinking market, OPEC low-cost oil producers, mostly operated by state-held national oil companies, should be able to maintain their market share and even expand it as higher-cost competitors falter.

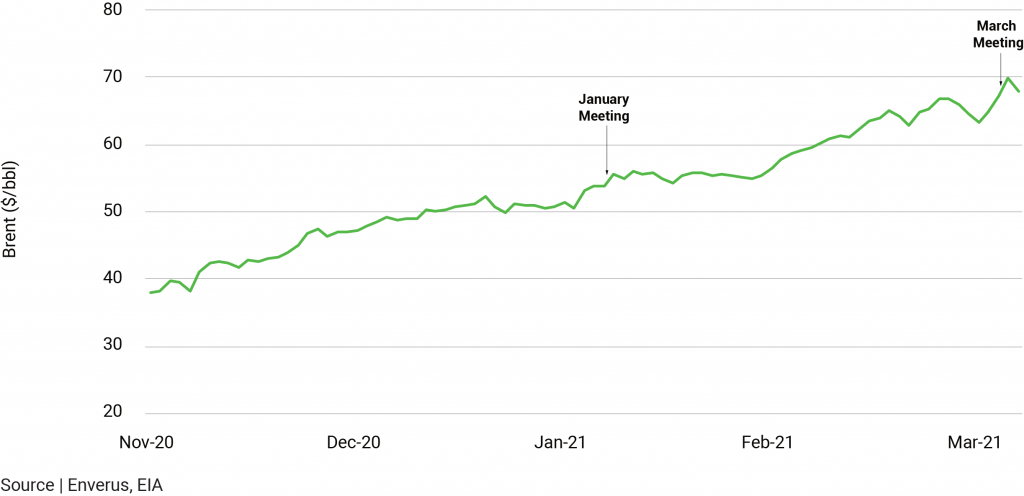

But if the volume outlook is broadly positive, OPEC producers’ oil price hawkishness comes at a price. OPEC’s readiness to extend an oil rally that has lifted Brent $15/bbl so far this year (Figure 1) is creating tensions with some of its key strategic customers. Indian government complaints about high oil prices drew a somewhat undiplomatic response this month from Saudi officials, who proposed Indian refiners draw down cheap oil stocks purchased when crude prices were at their 2020 lows. Saudi officials justified its hawkish price stance by pointing out that producers were only now recouping revenue losses incurred last year.

Saudi Arabia primed Brent’s rally through its slow and cautious return of output cuts, conservatism it justified by pointing to a raft of uncertainties besetting the global economy. But Riyadh has been less quick to acknowledge that a building headwind to economic recovery post-COVID-19 has been the sharp run-up in commodity prices themselves, particularly energy. For oil, it has been unilateral Saudi cuts this year and Saudi pressure to slow the return of OPEC+ cuts that has driven oil prices higher and roiled consumers.

Unsurprisingly, Indian government officials were unimpressed. Delhi has now injected fresh momentum into efforts to diversify its sources of crude away from Middle East producers. February import data suggests this policy is beginning to bear fruit with Indian refiners taking more U.S. and Nigerian oil at the expense of Saudi and U.A.E. barrels, where import levels were at multi-year lows. Further reductions to Saudi imports are evident in nominations for May deliveries.

Changes to Indian refiners’ import slates will not reduce oil prices, so diversification of imports is more symbolic than meaningful. But it does highlight growing tensions between the Gulf’s largest oil exporter and one of the remaining growth markets for exported oil. In this price cycle, OPEC producers might be advised to pay close attention: the removal of domestic fuel subsidies in recent years means Indian consumers’ capacity to absorb oil price rises is reduced.

At the same time, Iran, whose oil exports have been constrained by U.S. sanctions since the Trump administration withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal, is playing a very different game. With prospects for a diplomatic breakthrough improving, Iran has started re-engaging with Chinese buyers, particularly Shandong independent “teapot” refiners as well as Indian state and private buyers.

Iran has a long history of sweetening terms for its crude by allowing buyers to pay in local currencies, take advantage of deferred payment terms, use barter arrangements and offer price discounts. Whether such a flexible approach reflects Iran’s immediate need to carve out its market again or whether it will endure longer term remains an open question. Iran is unlikely to miss out on the opportunity to undercut competing Arab Gulf barrels, even if temporarily, in what is likely to become a febrile oil market for producers in the years ahead as demand shrinks.

From the Saudi perspective, the continued recovery in demand means extra Iranian barrels will be absorbed and that short-term discounting presents less of a challenge. As annual oil demand shrinks and flatlines, these kinds of behaviors will raise tensions both between petrostates and their customers; and also between producers themselves, increasingly chasing the same customers.

FIGURE 1 | OPEC+ Meetings and Brent Price