Equity markets go down 10% in a day, then stage the biggest rally ever seen.

Then they go down again. Then they rally, only to lose ground in the next trading session.

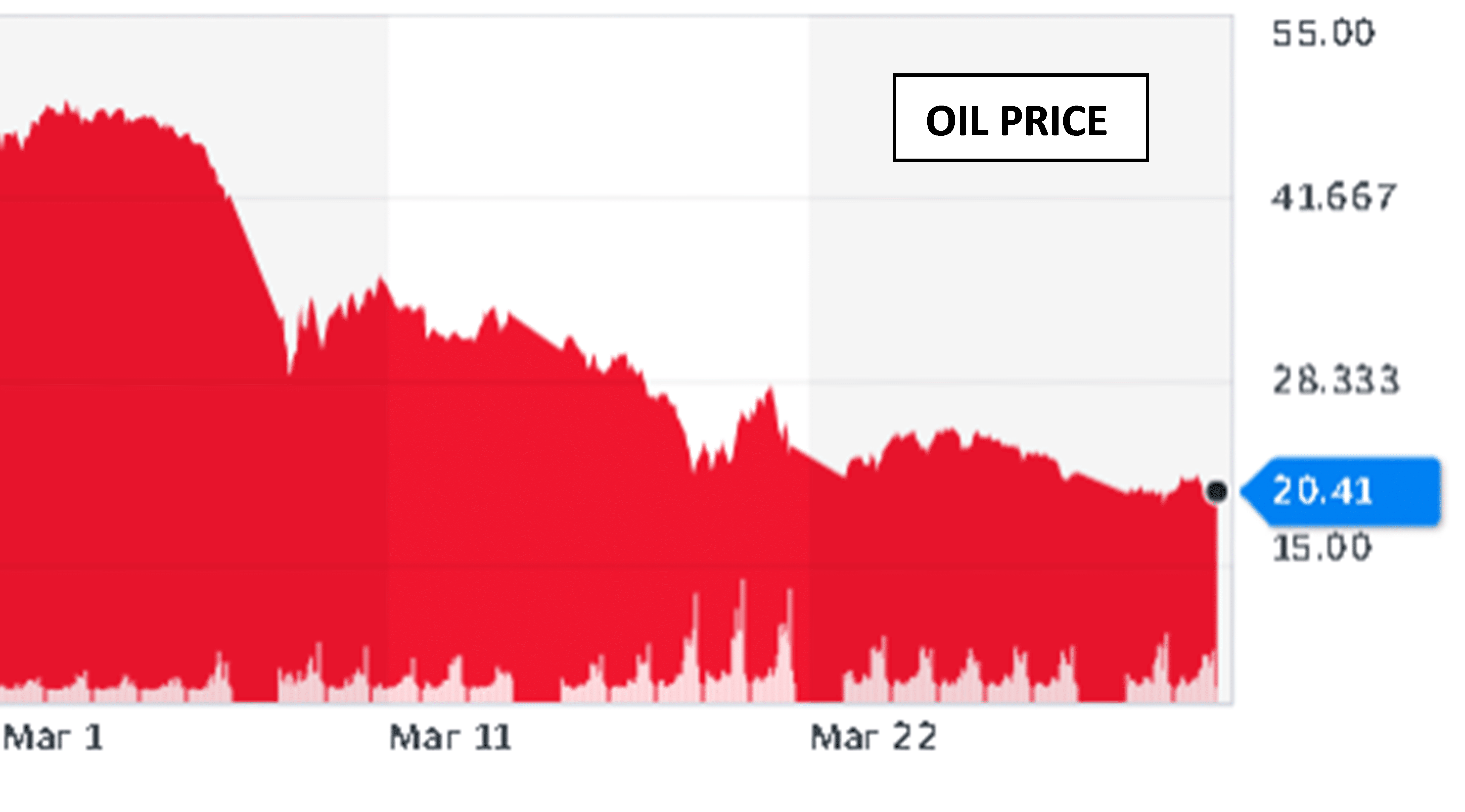

And oil prices? Same story.

From March 5-18, prices dropped by nearly 60%. From March 18-20, prices rose by 35%—no doubt due to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) formally soliciting bids for filling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR)—then dropped the same percentage from March 20-31, in tandem with the S&P 500’s drop due to demand destruction fears due to COVID-19.

Perhaps the oil price gains after the SPR announcement were immediately tempered by the realization that most of the storage available can only accept heavier, sour crude. Since most of the U.S. supply surplus is composed of higher API gravity—sweet crude from unconventional plays—federal purchases for the SPR likely won’t have a lasting effect on prices.

Oil markets are in a unique vise—COVID-19 and tariffs combined have dampened demand projections, and Russia and Saudi Arabia’s decision to flood the market with oil have dumped even more oil into a market that is oversupplied. Saudi Arabia said it is ready to add another 3 million barrels of oil per day into the markets. For perspective, this is equal to about 76% of Texas’ total December 2019 production!

Apparently, the Texas Railroad Commission is considering stepping in to limit Texas production and reduce supply, therefore firming up prices.

At first glance, it may seem like a good idea. But as is always the case—the devil is in the details. How willing will a highly indebted company be to curtail production when they need revenues to pay their loans? Will other oil-producing states, such as New Mexico, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Wyoming, Louisiana, and California also limit their production? Or will they adopt a business-as-usual posture and happily gain severance tax revenue—at Texas’ expense—when Texas tightens output?

As an industry, we’ve always weathered dangerous boom and bust cycles, and every single one of us has been through one before, buoyed by the optimism that sooner or later prices will recover.

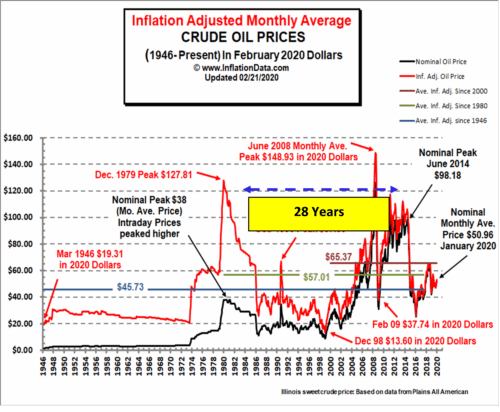

But will they? As the graph below shows, it took nearly 28 years (adjusted for inflation) for oil prices to return to the peak they had reached in December of 1979.

Note that after prices crashed during the Great Recession of 2008-2009, price reset came close to, but never achieved, the previous high. After prices crashed at the end of 2014, the following reset peak was 34% lower than the previous high in 2019. The NYMEX price has been hovering around $20 per barrel, which is only about 30% of the 2019 peak price of $65.37 per barrel.

Every energy industry professional likely has a prediction on where prices go from here. But if we’re all honest, we have no idea what structural changes in oil demand will occur as our societies move forward in a post-COVID-19 world.

Previous recessions saw companies find a way to get more productivity from their retained workers, dampening job growth post-recession.

As more and more companies adjust their operations and work models to keep their workforce at home, limiting or eliminating business travel, it’s quite possible they find their business processes going forward will require less travel and their workforces may become more work-at-home oriented. This would have a big impact on gasoline demand.

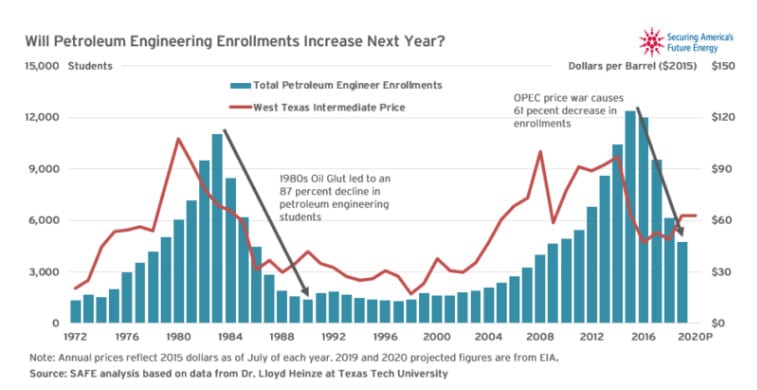

Perhaps a bigger worry is the future manpower supply needed to run the industry in the future. The graph below shows how closely petroleum engineering enrollments track prices.

Given that we’ve had four major price shocks spanning three generations, and an unclear outlook on the health of the economy and our industry over the next two to five years, it would not surprise me to see a profound drop in geoscience and petroleum engineering enrollments that may take years to recover to current levels—if it ever does.

If I was heading off to college and on the brink of committing my time and efforts to a field of study, would I want to train myself to enter an industry that has been consistently whipsawed over the past 30 years? It’s an exercise of daunting proportions to attempt to predict what standard workflows in the industry are going to be in two to five years.

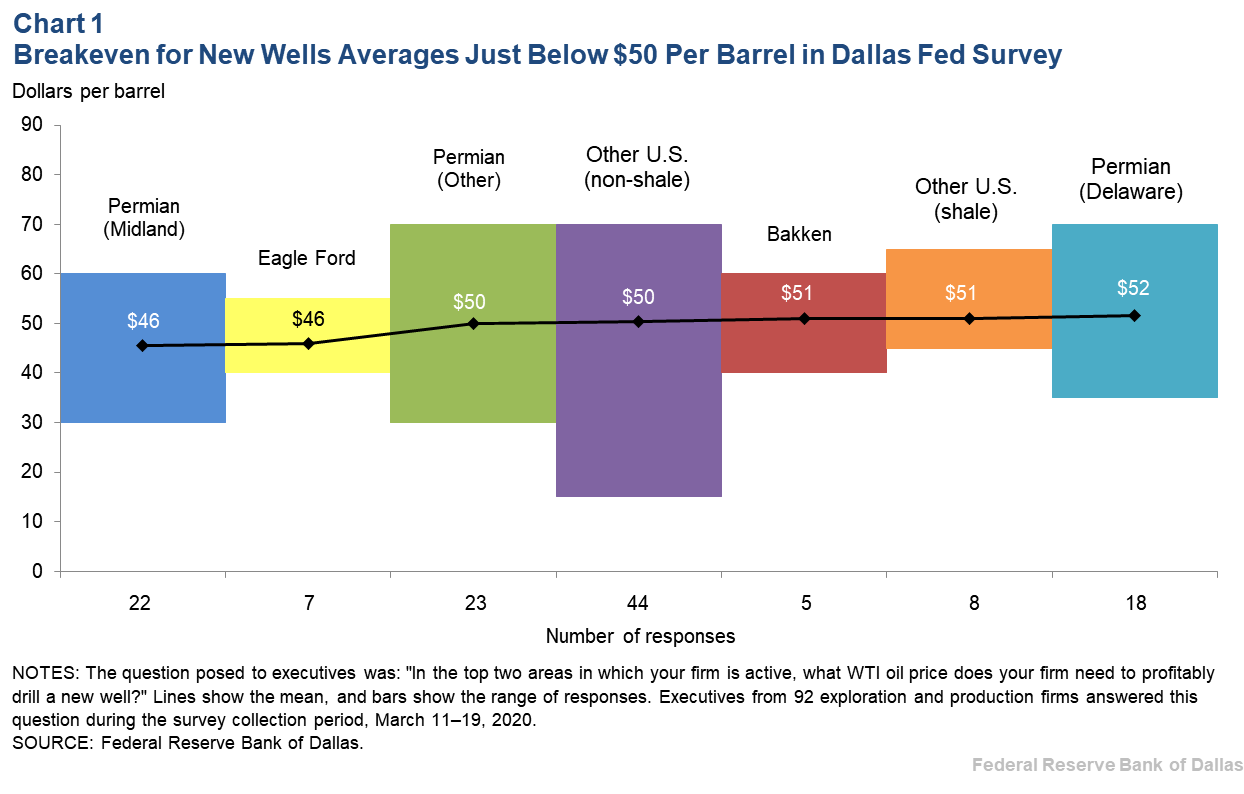

The Federal Reserve’s recent research report about attitudes in the industry confirmed that the usual bullishness we associate with the industry is gone. That’s easy to understand given the current price of oil on NYMEX and where survey respondents said prices had to be to break even. It’s even more understandable when you factor in actual prices paid at the wellhead per various company oil price bulletins.

If you download the Fed’s report and read through the comments, respondents who say their operations are mostly conventional were a bit more sanguine about the state of the industry. A few respondents even hinted at the “opportunities” in the oil patch. There was even a hint of levity when one respondent offered this: “What’s the difference between a pigeon and an oil man? The pigeon can make a deposit on a new Mercedes.”

Will debt issues force a massive consolidation of the business, implying a net loss of jobs? Will surviving companies, after consolidation, outsource most of their operations management to reduce payroll tax and medical and pension obligations?

Will risk management considerations make companies pivot away from low margin unconventional reserve exploitation and start looking at conventional opportunities that, while carrying greater “make-a-well” risk, have much lower drilling and completions costs and built-in price hedges due to much gentler decline rates?

How will industry workflows change? Will lessees be able to invoke force majeure due to COVID-19 to postpone drilling obligations?

The only thing we know for sure is that we have entered a time where the path to the future is unclear and filled with more uncertainties than we, as an industry, have ever encountered.

The silver lining to this cloud is that new opportunities are surely waiting to be exploited by those courageous and nimble enough to take a deep breath and reset their business models.