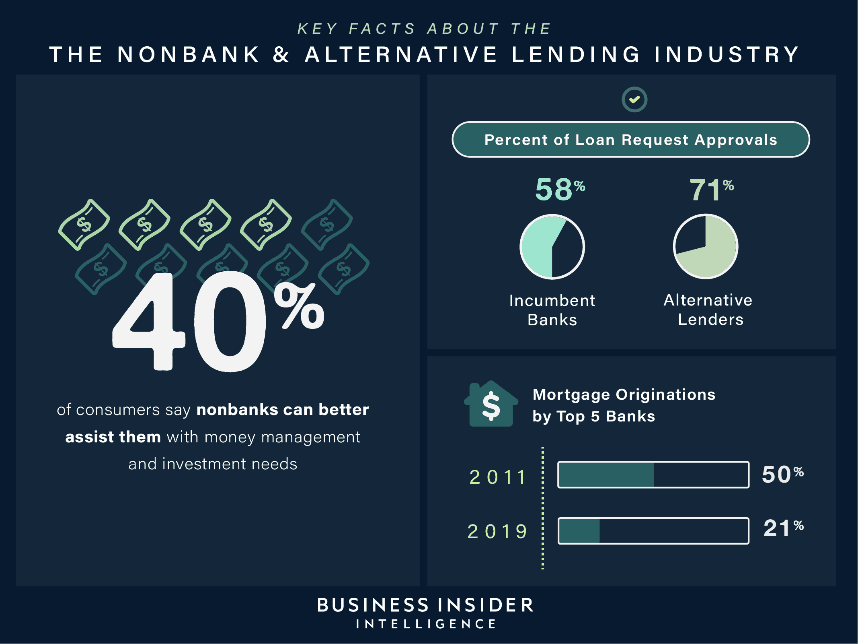

According to a recent study by The Economist, more than 44% of home mortgages in 2018 originated from non-bank lenders, compared to just 9% in 2009. It seems everywhere you look alt lenders will loan money at lower interest rates and in quicker time than a traditional bank. While banks have layers of bureaucracy to go through, and for good reason, alt lenders only have their financial backers to answer to.

Some alt lenders crowdsource their funding so all risk is on the individual, much like an investment vehicle. In reality, consumer alt lending is new to the market, but business alt lending is not. Oil & gas companies have always had creative, and sometimes confusing, alt lending structures such as DrillCos, overriding royalty interest (ORRI), and asset-backed securitization (ABS). Let’s take a look at these three structures to better understand where the market is heading in terms of alt lending for oil & gas.

Figure 1: Study on alt lending rise within the mortgage industry.

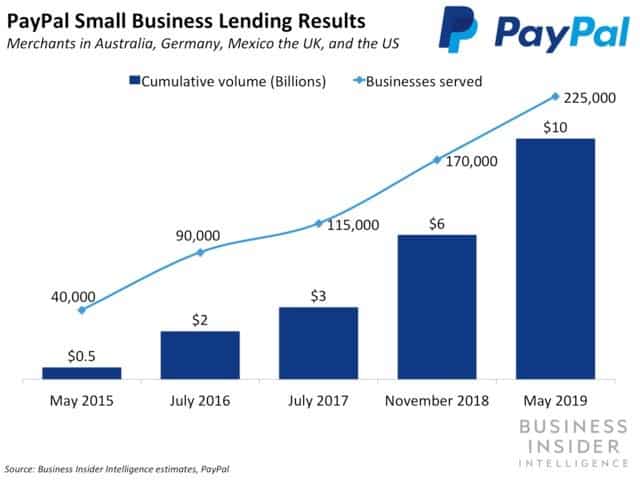

Figure 2: Alt lender PayPal growth of consumer loans.

DrillCos

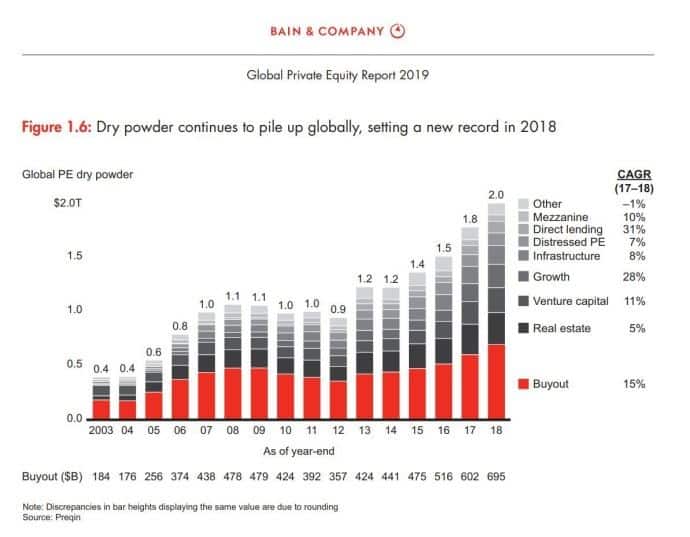

DrillCos are the oldest alt lending products for oil & gas. With the enormous amount of “dry powder” private equity (PE) has, and poor alternatives operators have to fund drilling, these have seen a resurgence recently.

Even larger independents use this structure on non-core assets that they don’t want to deploy capital or time to. It allows them to maintain ownership of the asset while lowering costs by turning the acreage to held by production (HBP) status. A DrillCo is where a financier will pay up to 100% of the costs to drill and complete a well for a certain percentage of the working interest that is reduced as hurdles are met. They will maintain a minority ownership stake in perpetuity, or it will convert to an override after hurdles are met. This allows them to receive the tax advantage of drilling a well with a long tail payout. A simple example is a financier providing 100% of the capital to drill and complete a set of wells for 75% working interest. This would mean the operator has a carried interest of 25% until hurdles are met. Once the hurdles are met, the financier’s interest is reduced until it is a minority interest, or it can convert to an override.

EOG employed this strategy in their Ellis, Oklahoma, acreage which allowed them to prove up the asset without deploying much of their own capital. If the DrillCo is structured correctly, there is a lot of upside left for the operator after the initial wells are drilled, holding acreage and lowering unit costs as infrastructure and locations are already proven. Other DrillCos announced include CRC Resources, EP Energy, Eclipse Resources (now Montage), and Ascent Resources. Some PE firms have raised exclusive funds for the deployment within DrillCos; GSO Capital Partners used $500 million in funding for Sequel Energy II which focuses on DrillCos.

For PE firms, a DrillCo allows them to put capital to work without the overhead management of internal teams. Their capital isn’t going toward grassroots leasing or the crowded world of bidding on an asset; instead it is being directly deployed into an asset and well. This creates instant value for investors and allows them to use tax advantages in regards to drilling expenses to further bolster returns.

Figure 3: Dry powder (committed) among all private equity companies.

Overriding Royalty Interest

Canadian E&Ps have used overriding royalty interest (ORRI) as a form of alt lending for decades, while this is just starting to take hold for public E&Ps in the U.S. Compared to a loan, an ORRI allows for the operator to shift some risk to the override buyer. With a loan, operators pay a fixed rate regardless of overarching commodity prices.

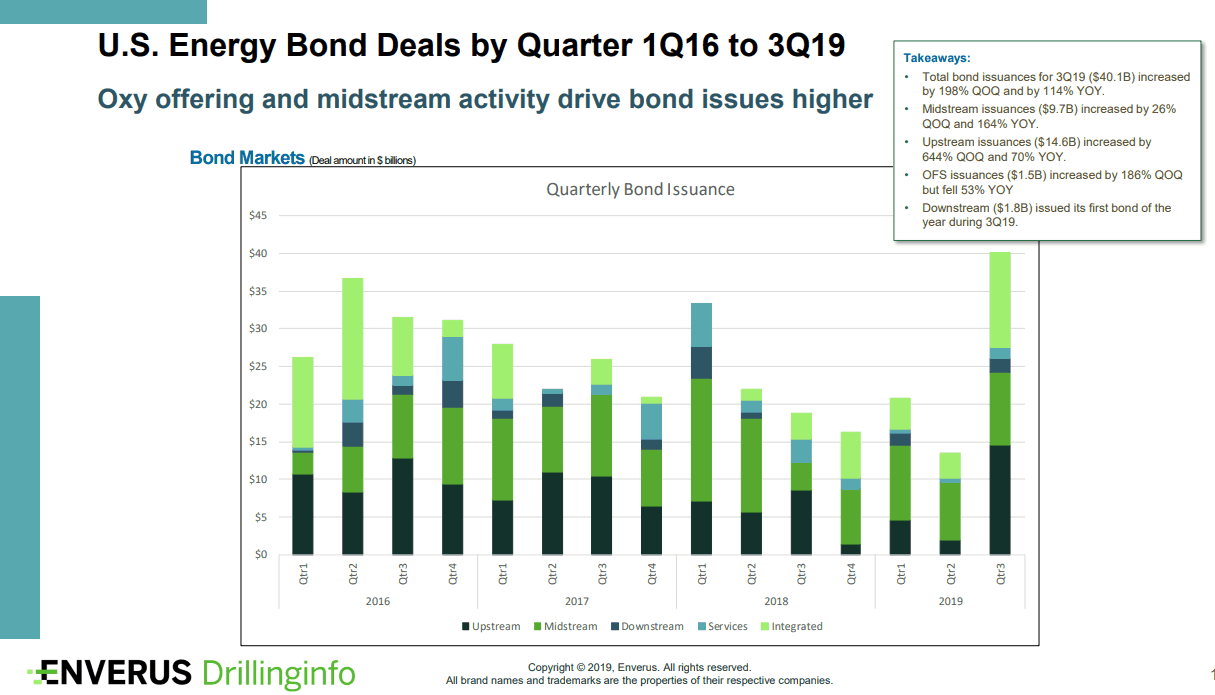

More operators are floating longer-term bonds to try and reduce near-term commodity and interest rate changes. An override for cash today, eliminates the commodity and changing interest rate environments as you pay a fixed amount of cashflow. This places more risk on the owner of the override and allows companies to remain flexible and not have to take on additional debt. Now, over time the override can be more expensive than a traditional bond or equity issuance, but since that market has been stagnant, operators must find other ways.

The prime example of an operator using an override to reduce debt is Range Resources. They have issued 3.5% ORRI, in total, for more than $1.15 dollars. In the near term, this will not affect much of their cashflow as the override is on 350,000 acres, which is not fully developed. In total, the cost net to them in year one will be approximately $85 million, but will allow them to reduce debt by $1 billion. The two buyers of the ORRI will continue to see their cashflow increase, or at the very least maintain, as Range continues to drill on the property and pricing recovers long term.

There is also opportunity for public mineral companies to participate in these ORRI financings. By partnering with a company in a basin, public mineral companies can secure long-term revenue without changing their business model. Operators in turn would receive the funding they need to reduce debt or increase drilling activity and the relationship becomes mutually beneficial. As more mineral companies become public, there will be a crunch in the market for deal flow to maintain growth and revenues; companies will have to come up with interesting ways to grow their business. Why not partner with an operator and own the drilling schedule?

Figure 5: Debt issuance in 2019 using Enverus Capitalize shows an all-time low until Q3 (Oxy and Exxon accounted for more than 50% of total issuance in Q3).

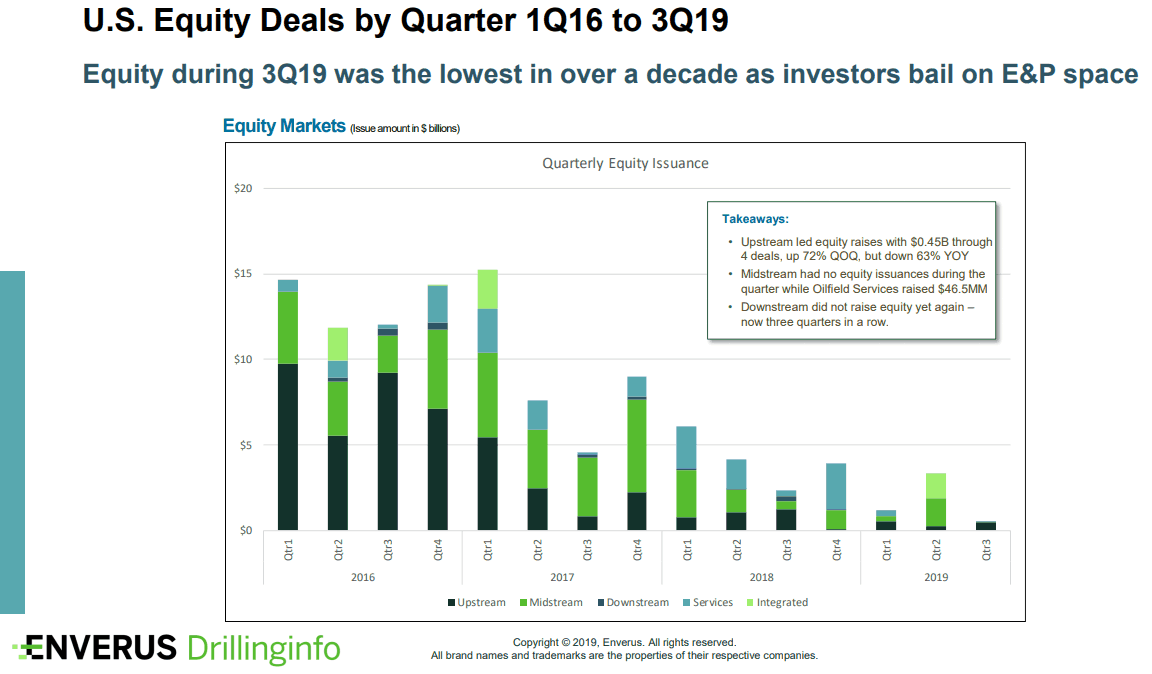

Figure 6: Equity issuance in 2019 from Enverus Capitalize report.

Asset-Backed Security

The newest form of alt lending we think might get some traction are asset-backed securities (ABS). By securitizing an asset, it opens it up to more investors looking for yield from a financial product that has an investment grade. Asset-backed securities also differ from other financial products as they are a financial product backed by a hard asset, such as royalty streams.

The benefit of an ABS is that risk is lowered as you pool together various streams of revenue that otherwise could not be sold on their own, for instance, hundreds of small royalty payments. The problem that will always exist for oil & gas is determining the value of the assets we own. Real estate is more straightforward, payments stay the same and delinquency rates are low for certain tranches while the underlying asset appreciates in value. Oil & gas assets decline over time unless new drilling takes place, but at the end of the day almost all assets go to zero.

Raisa was able to securitize non-op interests across 700 wells, which reduces risk of non-payment. It is much harder to show up at a well site and take ownership of your percent, however, than foreclose on a property. The ABS sold by Raisa has been compared to aircraft and railway issuances except, that those industries yield closer to 4.5% compared to Raisa’s ABS, which is 6% or more—meaning buyers are still unsure of the underlying risk of oil & gas assets.

There have been questions on how PE will exit their investments if the market is not willing to accept the multiples they request. One thought was that larger funds could create a separate debt fund to pay out investors. The problem is that this saddles PE-backed operators with a debt-loaded asset that reduces their ability to scale and grow. Many of these companies can get ratings on their debt, but it is still close to or at junk status. The ABS provides another avenue that would be open to additional investors on the street.

For mineral companies, both public and private, this might be one of the better routes to take if public investors won’t allow for additional debt or equity issuances. Since Raisa is the first one to complete one of these security issuances, it will be interesting to see if additional requests are made. If there is one thing the street likes, it’s new forms of investments to sell.

Will we see insurance products pop up if ABSs take off? Will there be other products similar to credit-default-swaps, as we see in the mortgage industry? Reinsurance? If (and it’s a big if) this takes off it will raise the question of to what limit will be placed on derivate products that are created, and that could create a house of cards.